Discussion of Bias and Motherhood

October 4, 2018

“How many people believe that there is a bias towards mothers in custody battles?” President of the Gamma Chapter of Omega Phi Beta Sorority, Incorporated (OPBSI) Katie Casado ’19 asked a room full of people. The majority of them raised their hands, indicating a belief in an institutional bias towards women when it comes to parenting in the United States.

This was a part of a larger discussion on Mother’s Privilege and parenthood that OPBSI held on Tuesday, September 25 in Bronner House.

“This event topic has never been addressed by the chapter or by the campus community, which is one of the initial reasons we had for wanting to put on the program. The idea just sprang from a conversation we were having about the differing culture surrounding Mother’s Day and Father’s Day; parents are celebrated very differently on these occasions.

We decided we wanted to ask the campus community why is it that we celebrate single and bash absent father’s on Father’s Day but don’t do the same with single fathers and absent mothers on Mother’s Day. Since our organization is about empowering women and educating our community, we thought this would be a unique way to discuss potential areas in our society where women are perceived to have institutional benefits over men,” Casado said.

After posing the question of bias towards mothers, Casado, along with her fellow OPBSI sister Yessenia Negron ’20, went on to explain how this perception of a bias against fathers is not all that it appears to be.

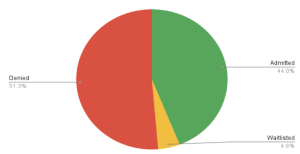

While 83 percent of single parents are mothers, only 40 percent of custody cases go to court, and of the cases that make it to trial, most of them rule in favor of the father.

“What looks like a bias against fathers is actually them eliminating themselves from the equation,” Casado said after reading off those statistics.

Many people in the room had different theories as to why this was happening.

Some suggested that it was the belief that fathers would inevitably lose a custody battle that compelled many of them not to try. Others argued that there is more leeway for fathers in this society when it comes to raising kids, so many of them opt not to.

“I think with single mothers they don’t necessarily get praised for for the work they do… but fathers, even those who aren’t single, get praised just for being with their kid,” Negron said.

Negron spoke about how there is a great expectation for mothers, especially single mothers, to be perfect parents.

She articulated how women are seen as negligent if they work while raising kids.

Another point of discussion that night was whether or not “maternal instincts,” or the natural inclination for females to be nurturing, existed. Some people believed in them, explaining studies done on female hormones during pregnancies and instances in the wild where new mothers nurture the children of their natural prey, such as cats and birds.

There were other people who did not believe in the existence of maternal instinct, and postpartum depression was brought up as an example as to how the notion of female maternal instincts does not always match up with reality.

“While I think there might be some type of mothering instinct to protect, it does wear off. It’s not like how we understand it,” Anna Harootunian ’19 said after bringing up adoption as an example of how parental instincts could be learned.

“Being a parent feels more forced upon women because they’re the ones who have to carry children,” Casado said.

“We try to regulate women through children… I think it would be crippling to feel like you have to have maternal instincts.” Casado noted that she has observed many white families hiring nannies. In some circumstances, she said, motherhood is looked down upon and women who vocalize their desire to raise their kids are ridiculed for it.

“It’s really interesting to see how race implicates what motherhood looks like,” Casado said. This statement was contested by a few of the people in attendance who attributed this difference to class.

“There’s certain boundaries I think a lot of people in dualparent households think have to be there… motherhood is associated with being nurturing and comforting and being there, while fatherhood is more like support from a distance,” Annika Eberle ’20 said.

For some, this stereotype was true. Melany Lucero ’20 spoke of how her parents receive criticism from their own families when they break gender roles. When she was younger, her mother was pressured not to take a job to help financially support the family and, as an adult, her father is ridiculed by his parents for doing “women’s work” when he helps out with housework and cleaning.

“I know my dad; he was really ashamed about that, especially around his part of the family,” Lucero said.

Many people also spoke of their supportive fathers who defied stereotypes.

“I feel like people have always put less expectations on him because he’s a black man and that contributes to him being there,” Jahnae Morgan ’21 said.

One thing that Casado drew attention to was the role that mass incarceration played in single parenthood — historically, many fathers, especially in African-American and Latino communities, could not raise their kids.

“Society has made it such a sensitive topic that if I talk about my dad, I feel like I’m bragging,” Melanie Jacquez ’20 said.

The night ended with theories on how to break gender stereotypes in parenting. One idea set forward by Negron was outlining clear expectations before having children.

Daniel Schratz ’21 spoke of holding fathers to higher standards.