The history of David Rossell, Union’s first enrolled black student

January 23, 2020

When David Rosell transferred to Union College in 1859, the alleged story is that the Southern student population found themselves angry that a black student had enrolled. Rosell did not disclose that he was black, but claimed that he was of “French and Indian extraction.”

This description was an excerpt from an article submitted to the Frederick Douglass Paper’s, but the article was written by Ira J. Clizbe—secretary of the Class of 1861. The New York Times reported on February 10, 1859: “His color was in fact so shadowy that it was thought he must be a mulatto, or at the very least a quadroon.” So if admittedly Rosell did not outwardly appear black, then this also disproves the lore that Southern students were angry that a black had enrolled, because they really had no way of knowing that he was even black.

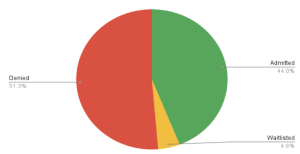

Regardless, not wanting to upset or agitate the Southern students, Union’s fourth president, Eliphalet Nott ordered that Rosell’s enrollment be decided by a vote of the student class. The vote turned out to be 34-24 in favor of allowing Rosell to stay. The New York Tribune reports, “Our venerable but prudent President said it should be left with the class. The class, by a majority of ten, decided this morning to admit; but now our President claims, absurdly, that the consent of the class must be unanimous.Therefore, Rosell was asked to leave. It is unclear whether Nott assumes the vote would not pass, and that is why he changed the vote to be unanimous after the fact. Furthermore, the New York Times article claims that once it was proved that Rosell was of Native American descent and “without a particle of African blood in his veins,” the decision to remove him was rescinded.

In addition, as if the situation was not taxing enough, the back-and-forth that Rosell was subjected to was humiliating, whether he was eventually allowed admission. A newspaper from 1859 reports that “all objection had ceased, and the young gentleman of color, Mr. David Rosell, is now a student in the ancient seat of learning which has produced such men as Hon. WM H. Seward and the Hon. Gerrit Smith. The world moves. There is hope that in that rote of the young gentleman of Union College.” And as previously stated, while this may have been a victory for Rosell, he did not choose to graduate from Union and from all other indications, did not decide to stay long at Union.

Furthermore, there are fundamental issues with the percentage of Southern students attending Union in 1859. The Class of 1860 would be put at 58 students. In addition, the total number of Southern students enrolled in 1859 was only four. Four out of 58 students would make Southerners only seven percent of the junior class. This is also assuming that all four Southern students enrolled at this time were members of the Class of 1860—which was unlikely. In addition, there is a large possibility that neither of these four students could have been in the Class of 1860—which would make the lore that the Southern students threatened Rosell out of school is false because of how few Southern students there were.

Therefore, the school was more complicit in allowing for Rosell’s dismissal than the Southern students. The Concordiensis from May 9, 1900 features an article titled “1860: Sketches of Union Men to celebrate the Fortieth Anniversary of their Graduation.” In this article, David Rosell is listed as one of those men. Each man gets their name, and around one to two sentences written about them. For David Rosell, the following is written: “David Rosell, Jr. M.D. Entered Union from Williamsburg and now resides at Brooklyn.” While this does provide some information about Rosell, it fails to leave out one important detail—which is that Rosell did not graduate from Union, and therefore was not celebrating his fortieth anniversary of his graduation.While this unfortunate incident stayed with Rosell, it did not deter him from seeking an education or becoming immensely successful as a doctor in his own right. From what is written about him, it appears that Rosell was an immense asset to the community in Philadelphia—not only because he was an excellent physician, but because he also was fluent in German. Despite this, Rosell’s career was successful as can be measured for a black man of his time—especially to be given so many opportunities, besides his time at Union. If only Rosell had been given the opportunity to stay at Union, one wonders what would have become of him.

Any questions regarding the sources of the facts in this article can be directed to the article’s author.