Artificial intelligence has become nearly unavoidable in everyday life with its growth over the past few years, and college education has not escaped its reach. Something that might have once seemed limited to sci-fi movies is now mentioned in syllabuses and frequently utilized in homework and studying, whether approved by professors or not. With its sudden widespread popularity, Union students and professors hold a mixture of opinions.

Platforms such as ChatGPT are often used by students, for tasks from solving tricky homework problems to summarizing pages of readings. Grace Kaiser ‘27, a History and Political Science Interdepartmental major, comments “I think there’s a lot of people that use AI at Union. I think it can be valuable to use for something like clarifying readings if you’re confused, but I am very against people using it to write for them.” She expands, “Using the words it produces is very disingenuous and antithetical to learning and developing skills, as opposed to checking your work.”

“I really don’t like AI, because it’s really bad for the environment,” states Psychology major Cailyn Buckley ‘27. It is true that the rise of artificial intelligence has a significant environmental impact: massive amounts of electricity are needed to train and run AI models, and this energy is generally sourced from current power sources relying on fossil fuels rather than renewable energy, resulting in large greenhouse gas emissions. Powering these models also consumes large amounts of water, used to cool data centers as heat is generated by the substantial processing demands.

“I have mixed feelings about AI,” explains Computer Engineering major Sami Foodim ‘27. “I think it’s really helpful when it comes to creating study guides and practice exams, but it’s also really easy to blur the line between what’s academically ethical and what isn’t. In our generation especially, I think that line is becoming increasingly blurred.”

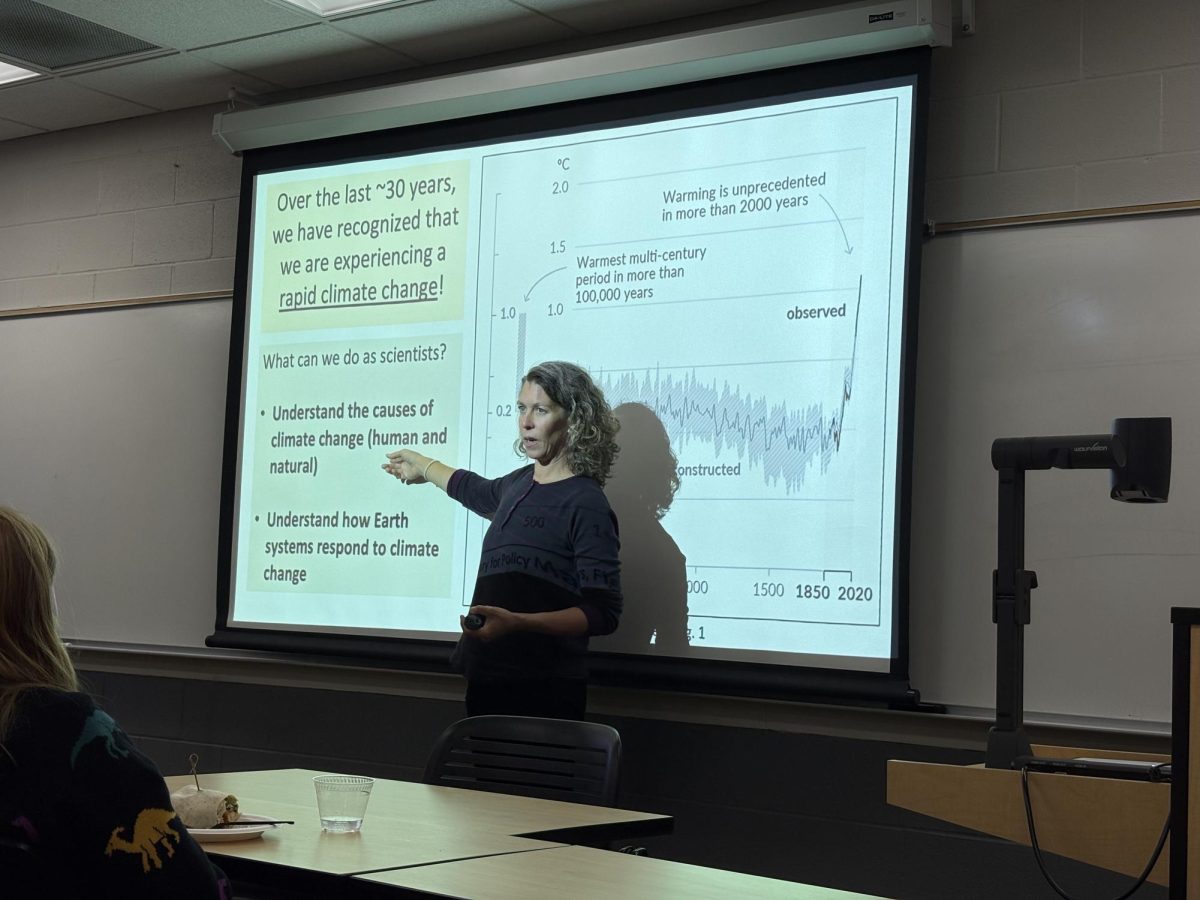

While many professors dissuade their students from using AI in their assignments, others embrace this new technology. Professor Miyawaki of the Geosciences department explains, “I see AI as just a tool, like how the calculator changed the way we do math. I think it’s here to stay, and that people who graduate from college in one way or another are going to use AI. My philosophy is, do we want students to have experience and know how to use AI effectively, or just be told we can’t use it at all? I align more with the former- it’s not flat out bad, and it can be used in a way that doesn’t offload all your thinking. I think most students would use it in that way if they had more practice and guidance on how to use it.”

He approaches AI with an open perspective, explaining that he has students use it from the very first day of class to investigate a specific environmental concept. By comparing its answers across multiple AI platforms and with a search using scientific sources, they are able to see that its responses can be fairly consistent. However, they also find that it’s often incorrect for further tasks such as writing code, helping students see for themselves where both its strengths and limitations lie.

Professor Miyawaki continues, “AI is actually doing a much better job explaining things in an easy to understand way, because if you go to these scientific sources, a lot of the time they just introduce more and more complex concepts. It creates a rabbit hole for you to dig further into, but doesn’t actually answer the question you wanted to get at. Students then understand the power of AI as a tool to get information.”

“There’s a lot of learning opportunities there, where you need to use AI in a way that you can judge it and question what’s coming out of it, so that you don’t outright trust everything it says,” he notes. “The more opportunities students have to go through that experience, I think the more they realize what it’s useful for, and what it can’t do.”