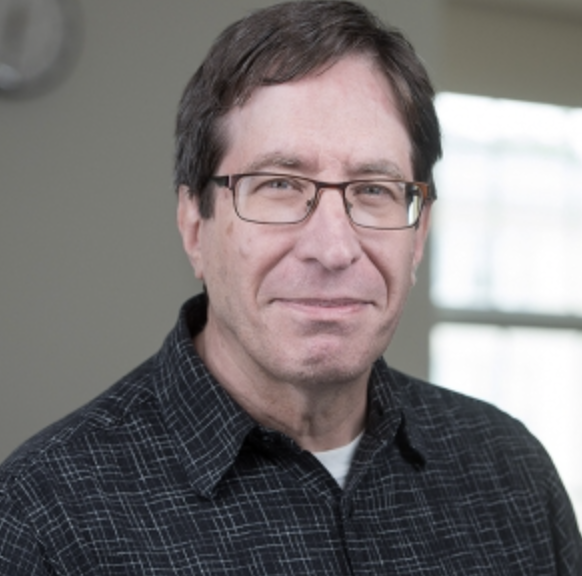

After almost 36 years, Professor Leo J. Fleishman will be retiring with the end of the 2025 academic year, marking the end of his time as a part of the Biology department here at Union College.

While teaching courses ranging from Topics in Physiology to Animal Behavior, Professor Fleishman carried out research investigating animal communication through visual signals and how they are perceived. His work delves into how organisms (frequently lizards) detect and process information like motion and color from the world around them, and the role it has played in their evolution.

In a short Q&A, Professor Fleishman reflects on the path that led him to this career, memorable highlights from his time at Union, and words of wisdom for the generations of students to come.

What led you to the field of animal communication / perception?

I was an animal lover as a kid for as long as I can remember. I had many pets—hamsters, gerbils, lizards, fish—while I was growing up. I cannot remember exactly when I became fascinated by communication, although I was a big fan of Dr. Doolittle books. (Dr. Doolittle was the British doctor who was taught by a parrot how to talk to all animals.) In college, for my senior research, I tried to show movies to fish to decipher how their threat displays enabled them to settle fights. The experiments did not work, and I began to wonder if the way they perceived color, depth, and motion might differ from humans.

After graduating college, I got a job working in the tropics. While there, I got to see lots of small lizards signaling to one another. I became entranced with lizard communication because they are so colorful and their movement patterns have a hypnotic effect. Then, in graduate school at Cornell, I took a course on animal communication that examined the relationship between sensory systems and signals, and that got me thinking a lot about visual processing and its role in communication. Finally, when I started my research at Union, I began to think about the role that the environment and the visual system played in causing the evolution of signal diversity, and I’ve been pursuing that question ever since.

What were some of your most memorable experiences during your time teaching and doing research at Union?

My most memorable teaching experiences occurred when I was leading trips to other countries. I taught a 3-week course on tropical biology that traveled to Panama. One year we traveled on horse-back to a remote jungle field station. While we were there, it rained for several days in a row. When we returned, we had to ride horses down a mountain through the rain and the mud. The horses were slipping and sliding the whole way. It was terrifying and exhilarating.

My other big international teaching opportunity was directing the term abroad in Australia one year. I loved everything about that country, and we encountered so many interesting animals and amazing landscapes. It was a thrill to travel with students to so many amazing locations.

Is there any message or advice you want to give students?

A few things come to mind: First, everyone’s path is unique. You have to find your own way forward. The best advice I can give is to work hard and follow your passion. Opportunities will present themselves, and you should grab them.

Second, become political. Right now the country and the planet are in trouble and it is up to our young people to save it, and that means you have to engage. There are two sides to the debates about the future of our climate: the wrong one and the right one. Pay attention to what leaders are saying and vote vote vote!