Following a highly controversial transition of presidential power, the 2025 Super Bowl LIX occurred during a period of heightened international political tension. Pulitzer Prize-winning artist Kendrick Lamar is no stranger to this discourse and elected to perpetuate the conversation by incorporating culturally significant allusions into his Super Bowl LIX Halftime performance. The show featured excerpts from ten of his most culturally significant songs.

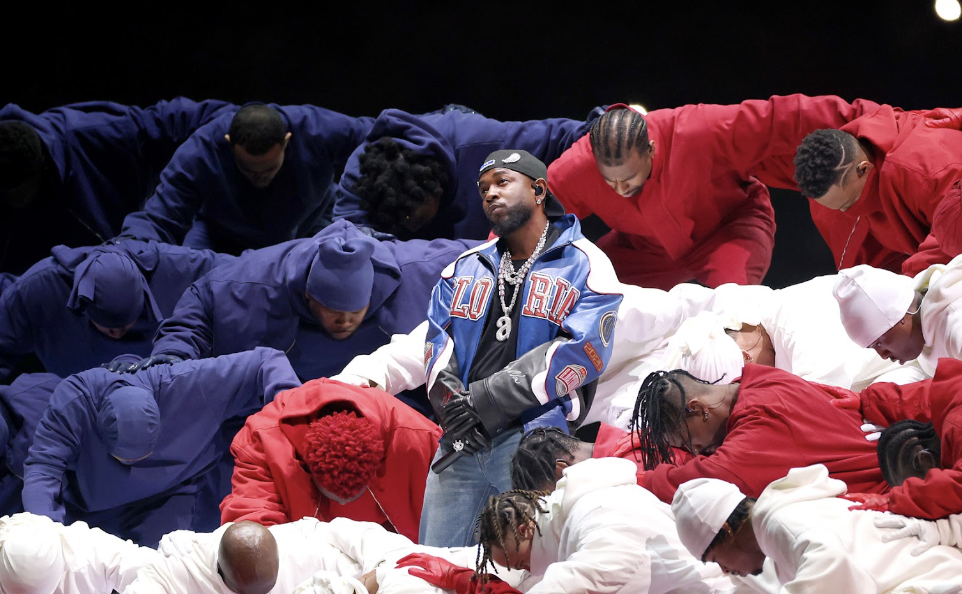

At the performance’s onset, Lamar delivers a sneak-peek into his unreleased song, “Bodies,” a long-awaited constituent of his 2024 album, “GNX”, which discusses themes of systemic oppression and Black culture in America. The album is further referenced as Lamar stands atop a vintage Buick Grand National Experimental. With the help of trap doors, Lamar’s “army” of backup dancers emerges from the car and disperses across the stage, each individual adorning one of three monochromatic ensembles: all-red, all-white, or all-blue.

From his vantage, Lamar recites, “The revolution is about to be televised.” This lyrical prelude references activist Gil Scott-Heron’s song, “The Revolution Will not be Televised” (1971), which, at the time, reinforced the need for protest in local communities during the Civil Rights movement. For Scott-Heron, complacency in the movement was not an option. Lamar reworks the meaning of this statement, however, by utilizing television as his platform to amplify the disruption of America’s repressive condition and call for cultural equity. He continues, “You picked the right time but the wrong guy”, potentially indicating to President Donald Trump – the first sitting president to attend a Super Bowl game – that his performance would be culturally disruptive.

The performance immediately addresses the nature of Blackness in contemporary America. Samuel L. Jackson, a prominent Black-American actor known for his appearances in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, plays Uncle Sam. His role parodies the societal “requirement” that Black Americans must adhere to the American system. Throughout the performance, Jackson arrives to criticize Lamar’s expression of frustration and unrest that pervades disenfranchised Black communities.

Choreography by Charm La’Donna largely contributes to the performance’s symbolism: In transitioning to the song “Squabble Up,” dancers approach Lamar from opposite stage ends, shifting their previously relaxed movements to configurations that resemble a resistance to physical force. “Squabble Up” takes on a new meaning here: Marginalized peoples must now respond to repressive regimes. Ironically, the dancers then inhabit more militant positions (almost saluting to the American system), representing the Black community’s historical and protective yield to subservience.

Displeased with this display, Uncle Sam condemns the performance as “[too] loud” and “too reckless.” By now, it seems that “the game” refers not only to Lamar’s encounter with the custom of Black obedience but also to the overarching sequestration of Black expression; Black existence is only “acceptable” when undisruptive to the American condition.

The set then transitions to the song “Humble”, which Lamar uses to demand that American audiences reduce disproportionate displays of privilege to abate socioeconomic divides between racial communities.

Two squads of dancers, interrupted by Lamar’s presence, assume the image of an American flag. It seems that Lamar recognizes the polarized political discourse that has been amplified in recent years – with the condition of marginalized communities existing at the center of tension. Consequently, each time the artist repeats the phrase “sit down, be humble…” the dancers descend a set of stairs, perhaps referencing the need to dismantle an overbearing government. Or rather, relieve the Black community’s continued compliance with discriminatory behavioral standards.

During “man at the garden”, dancers reference choral singing – a common cultural practice – when Uncle Sam condemns their display and turns to the camera, saying, “Scorekeeper, deduct one life.” Jackson’s intervention implies that American audiences have the agency to determine the quality of Black safety so that exhibitions of Black culture can be sequestered by an Anglican call for cultural assimilation.

Lamar contends Uncle Sam by responding with a notable phrase of the night: “It’s a cultural divide, Imma get it on the floor/ 40 acres and a mule this is bigger than the music/”, referencing the 1865 unfulfilled order that previously enslaved soldiers would be given 40 acres of land and a mule to kick start life after the Civil War.

Of course, this dissection merely grazes the depth of Lamar’s performance and neglects to address many references to national culture and institutional behavior. However, it should amplify the warnings that prominent artists are advertising amidst periods of increased polarization and information censorship. An unfortunate reality remains: The American psyche has yet to accept Black liberation – and adequate treatment towards minorities – as a necessary and critical practice.