Holocaust speaker series: Max Eisen at Union College’s Chabad

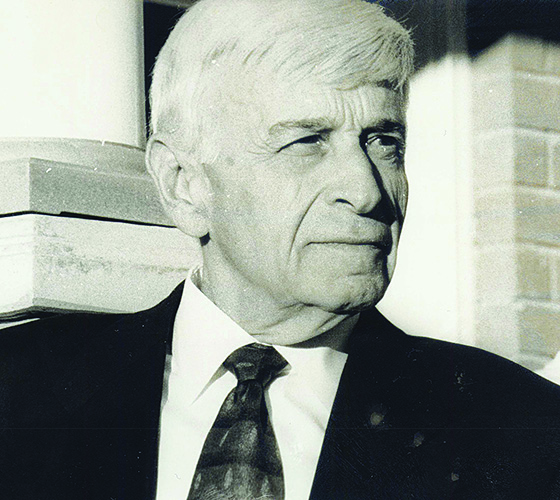

Photo of Max Eisen. Credit to Harper Collins.

April 22, 2021

Max Eisen’s presentation in cooperation with Union Chabad, the Union History Department, and the Religious Studies Department on Monday evening came with a stark warning: hate that begins with words can easily become unspeakable violence. Eisen, born to a Hungarian-Jewish family in Slovakia before it became subsumed into Hungary after the German invasion and partition of Czechoslovakia, would eventually be imported to Auschwitz-Birkenau were he would be enslaved as a forced laborer until the removed from Auschwitz to Austria, where he would be liberated.

One of the things that stood out in addition to the description of the brutal conditions in Auschwitz was the banality of the collaboration with the Nazi Regime Moldava, the town in which Eisen lived had a population of 5,000 including 90 jewish families. When anti-Jewish racial laws came into effect in Hungary, stripping the jews of their buisnesses and property, their neighbors spied an oppurtunity and seized the property of their neighbors under the watchful eye of the newly installed Hungarian Gendarmarie. This included Eisen’s father, who was run out of his shop by a previously cordial neighbor. When Hungary was invaded by their former ally Germany in March 1944, the jews, previously protected from deportation to the camps, were now under threat. On the second night of Passover, April 9th, 1944, the jews from the town were brought to the local school, where they were forced to spend the night. Eisen called it a bitterness without maror (the bitter herb of the Passover dinner.) The next day, the jews were moved from the school to the train station, all the while heckled by their former neighbors. From there they were loaded into cattle cars, packed tightly enough they were left without room to do anything but stand. The journey from Slovakia to Auschwitz was four days, and all the while, the jews in the cattle cars stood. For all the jews who would be brought by train to Auschwitz-Birkenau, there was never a single instance of sabotage against any of the trains.

It is at this point that anything that could be considered to be banal evil fades away and is replaced by the utter darkness that was Auschwitz-Birkenau. Upon arriving, the jews would be sorted by an SS officer. If you were directed one way, you were moved to a barracks to become a forced laborer. If you were directed the other way, you were brought immediately to the gas chambers. Eisen’s mother and three siblings, two younger brothers and a baby sister, were directed to the gas chambers. Eisener, fifteen years old in 1944 and his father were spared for the time being. Slave labor in Auschwitz was brutal. Prisoners were given rags to wear and starvation rations, only 300 calories a day. Individual barracks would be “quarantined” and then the inhabitants would be marched to the gas chambered. Such was the fate of Eisen’s father and uncle. Eisen survived by chance. After collapsing in a field from exhaustion, a crime that might have led to his execution, Eisener was saved and brought under the aegis of Dr. Tadeusz Orzeszko, a Polish prisoner who worked as a doctor in the camp. Eisen was given the job of keeping the Orzeszko’s operating room clean.

As the Red Army came close to advancing on Auschwitz-Birkenau, the Nazi government liquidated the camps in January 1945, moving the remaining prisoners westward towards the center of Germany on what are known as the death marches. Eisen was brought to a camp by Ebensee. In mid-April, the remaining SS guards locked the doors of the camp and fled, leaving the starving prisoners inside. On May 6th, members of the US Army’s 761st “Black Panther” Tank Battalion liberated the camp. There is a photo of the liberated prisoners of Ebensee that was shown during the presentation. They are huddled together, their faces gaunt. They are only wearing dirty rags that cover their torsos. They are only skin and bones, including their knees, where their knee bones were noticeably wider than their legs. Eisen is not in this photo, he had collapsed right after the camp had been liberated, when he realized that he had survived.

After Ebensee was liberated, the prisoners were tended to by various hospitals across the region. Eisen ended up being brought to a hospital along the Austro-Czech border, where he was able to partially recuperate. When he was well enough to walk and hold down food, he made his way back home. He was one of less than twenty jews from his town to survive. Realizing there was little left at home, he relocated to Marienbad spa, near Prague, which was serving as a hospital to former jewish prisoners. While recuperating there, the new communist Czech government enacted conscription and closed the border trapping Eisen and the rest of the Marienbad group. They tried to escape across the border, but were caught and sentenced to 25 years in prison, only being released after a jewish aid group paid $2000 per person as a ransom. From there Eisen fled to Salzburg, Austria and then to Canada, where he lives today.

For 32 year, Eisen has worked to prevent the growth of antisemitism and prevent another holocaust. He gives lectures to students and congregations and lobbies on behalf of this issue. In 2016 he published his memoir By Chance Alone. But Eisen still worries about the rise of antisemitism in today’s society.