Faculty retirement benefit cuts and endowment mismanagement

March 11, 2021

****Any views expressed in this article are solely the opinions of the writer, not necessarily the opinions of the Editorial Board of the newspaper.****

On January 29, I attended an open office hours session with President David Harris during which a senior Schaffer Library employee asked when she might expect to receive her next retirement pay. The 11 percent contribution, a contractual benefit, had been cut for most staff and faculty over the summer, despite a 127 faculty-signed letter which had urged reconsideration. The letter laid out a variety of objections to the austerity measures, questioning the necessity of the cuts and proposing alternative strategies for managing the budget. It was in this context that the librarian posed her question to the administration, to which President Harris replied, “We had to make cuts due to budgetary challenges. We may face similar challenges in the future. Benefits will be reinstated once those challenges are met and properly dealt with.”

In the moment, this made some sense. But upon further scrutiny, I think the logic falters. The faculty and staff signed a deal for their labor and expertise with Union College, a deal which the institution has since reneged on. Decisions like this require explanation on behalf of the Board of Trustees.

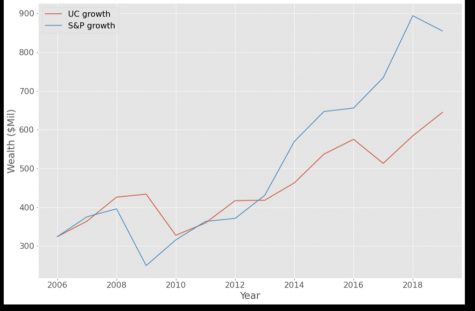

Recent research on our endowment from Professor Eshragh Motahar, from the Union College Economics Department, questions many of the claims made by the college in defense of these decisions. Using publicly available data, he found that from 2006 to 2019, Union College spent an average of 6.5 million U.S. dollars annually in investment management and incentive fees, placing our school in the top 6 percent of all institutional spenders on a normal curve study in that particular budgetary category.

For those fees, our college received an average of 3.4 points below S&P 500 value on an annual basis, underperforming our peers. What’s more, if we had simply only invested in S&P for that period of time, our returns would have been 189 million U.S. dollars greater. With this information in mind, the decision to cut retirement benefits appears questionable. Had the Board of Trustees passively managed our endowment those retirement cuts would not have been necessary.

Despite recent interviews with administration on the issue, a variety of questions still remain. Firstly, we do not yet know who the recipients are of those high fees. Additionally, we do not know why the fees are so large or what metrics the college is using to determine appropriate fee totals. When I asked President Harris what justified the high fees for such low returns on January 23 and on January 29, he explained the endowment issue using a real estate analogy. “It doesn’t matter what you pay the realtor,” he tells me, “it’s about what you clear on the house.” I would like to consider this for a moment.

Our endowment is performing on average 3.4 points below market while our fees are much larger than our peer institutions on a peer reviewed normal curve. Further, as Professor Motahar’s analysis indicates, “In the period between 2006 and 2019, fees as a percentage of endowment increased by 109%, displaying a statistically significant upward trend, while performance showed zero trend.” In other words, there is no correlation between the increase in fees and returns on our endowment. What then explains the increase in fees?

An additional question concerns the nature and location of our investments: on any given year the college invested between 39% to 55% in Central America and the Caribbean. I would like to know why that is.

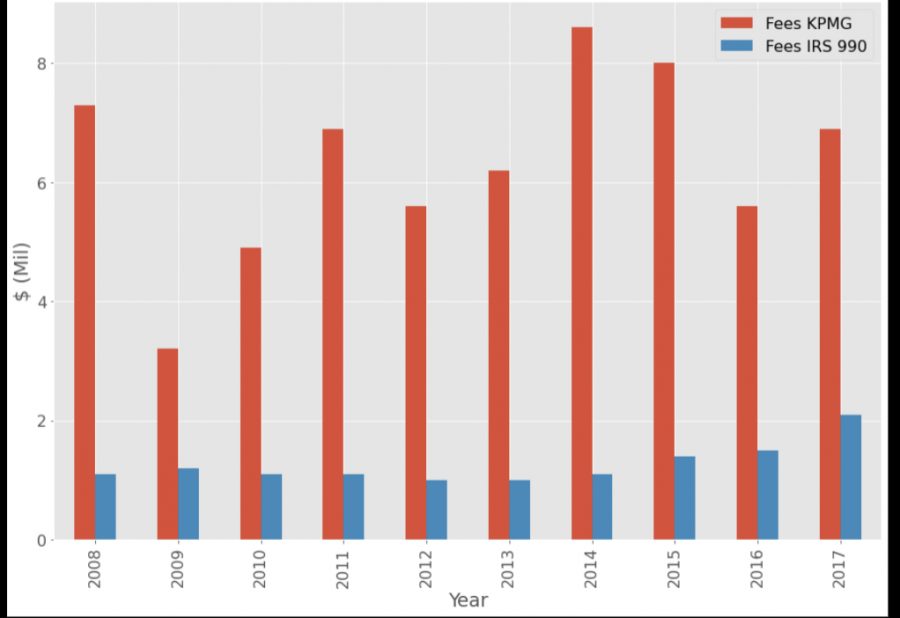

There is also the issue of fee classifications, existing as two separate categories of “investment management fees,” which are reported to the IRS, and “incentive fees,” which are only reported on the annual KPMG report. In the accompanying graph of the difference between those fees for the studied period of time the existence of “incentive fees,” as a distinct category with much higher totals than IRS reported “investment management fees,” is confusing. I would like to know what determines the classification of these separate fees and if the college plans on disclosing future fees of this nature to the IRS. Responses from the relevant decision makers would comply nicely with our institutional policy of “transparency and accountability,” highlighted in our Strategic Plan.

Returning to the retirement cuts, it becomes clear that private risks taken at the level of a discrete board had consequences for the livelihoods of many in our campus community. Those risks have been socialized in the form of schoolwide budget cuts.

One can additionally wonder if these management practices have had other consequences on our budget, like the fact that at Union, we are only able to pay many full time dining staff a total of $12.60 an hour, a situation which forces many to take on multiple jobs and rely on overtime pay (additional working hours). If we had invested our endowment properly, would we perhaps be able to pay a $15 living wage to those hard working members of our community? One can and should apply this logic to a wide range of institutional expenses from academic hiring to tuition costs.

We can clearly see that decisions that the board makes, while done in isolation and with discretion, have consequences well beyond their table. And the reverberations from their decisions, whatever they are, always flow down even to the lowest levels of the institutional hierarchy. It’s what makes these issues particularly political.

I urge our campus community to pay attention and ask further relevant questions on behalf of those who cannot.