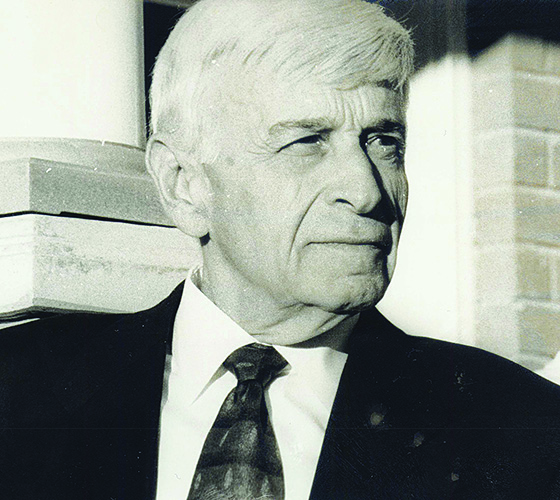

Dr. Bernd Wollschlaeger was born in 1958 in Germany to a mother who had been forced out of Czechoslovakia during the war and a father who had been a highly decorated Nazi tank commander.

During Wollschlaeger’s life, he converted to Judaism, renounced his German citizenship in favor of Israel citizenship and moved to Aventura, Florida in 1991 to start his family and work as a board-certified physician. He kept his family history to himself until one day, his son asked about his grandparents.

Wollschlaeger explained that he was faced with the question of how to explain to his Jewish son, who was raised in a modern Orthodox community, that his grandfather was a Nazi. Wollschlaeger’s answer was to tell his life story.

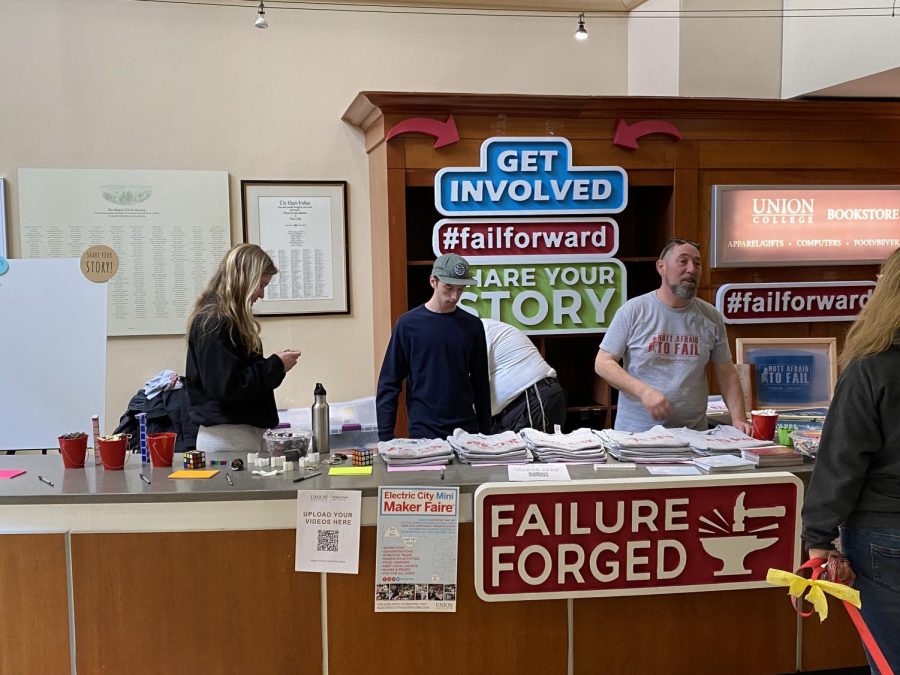

He told this story to Union students and members of the local Jewish community on Wednesday, April 25.

He began by describing how German education about the Holocaust changed during his lifetime and contrasting it with the stories he heard at home from his parents.

“One thing I noticed when I was a little munchkin, maybe seven years old…were that certain aspects of German history were taboo. There’s a word in German to describe it, totgeschwiegen: silenced to death,” Wollschlaeger said.

Wollschlaeger grew up hearing two different stories about World War II. His mother, who was an ethnic German living in the Sudetenlands, recalled the war as a period of chaos, violence and instability.

His father was a tank commander in an elite unit in the German Army who still believed in the Third Reich.

“My father told me… over and over again the same story of him serving as a tank commander in an elite tank unit in the German Army… he pushed the… way into Moscow, conquering a city called Morel. And for that accomplishment he was awarded the Knight’s Cross by a man whom he still adored, he referred to as his Führer, Adolf Hitler,” Wollschlaeger said.

Growing up, Wollschlaeger was not taught about the Holocaust. He learned in school that Hitler was a dictator who rose to power in 1933 after being elected a member of Parliament. He was taught that Hitler started the Second World War and persecuted minorities and intellectual dissidents. He was also taught that six million Jews were collateral damage in the war, but was not taught about the systematic extermination of European Jewry.

“On the eighth of May of 1945, the Nazis disappeared like the Huns invaded and exited Germany and we started our life anew. That was, of course, a concentrated horse manure story and it made no sense, except, of course, we were Democrats… and I grew up with that knowledge,” Wollschlaeger said.

Wollschlaeger began to question German history after the 1972 Olympics. These were the first Olympics hosted in Germany since the 1936 Games, which took place under the Nazi Regime.

Prime Minister of Germany Willy Brandt was a Socialist who had been persecuted by the Nazis and fled Germany from 1933 to 1945. He came to power after his predecessor, Kurt Georg Kiesinger, had resigned after his ties to the Nazis were revealed. Brandt had visited Auschwitz before the start of the Games.

“We were primed in school to recognize this event as an event that would separate the past from the present,” Wollschlaeger said.

At the Olympics, Wollschlaeger recalled the strange reaction of German adults to the Israeli team during the Opening Ceremony. He did not think much of this until the Munich Massacre occurred. Eight Israeli athletes were kidnapped and ransomed by an offshoot of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) known as Black September. Black September had been given assistance by the East German government. The West German government when negotiating the release of the Israelis, ignored the advice of the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) engaged in a firefight with Black September, and this resulted in the death of 11 Israeli athletes, coaches and a West German police officer. Wollschlaeger made a point to mention that Luttif Afif, the man negotiating on behalf of Black September, had a Christian father and a Jewish mother.

Wollschlaeger saw the 1972 Games as a “reckoning” for post-war Western Germany. The headline in the newspaper he saw the next day was, “Jews murdered in Germany again.” He had not learned about the Holocaust and did not understand what “again” meant. This was when he began to investigate his country’s history.

“Because of this horrific accident, our teachers, when I was 14 years old, started to talk about the past like I had never heard it before. For the first time, I heard words like Auschwitz… the Final Solution, the murder of six million as deliberate policy of a democratically elected government in the name of Germany,” Wollschlaeger said.

His father fervently renounced this paradigm shift, calling the Holocaust a lie and telling the high-schooler that his teachers were communists. Unsatisfied and untrusting of his alcoholic father’s story that all the Jews killed by Germany had been “enemy combatants” and that Germany had “done the world a favor” by committing mass murder, Wollschlaeger searched for his own answers.

“I asked one of my teachers, a former Jesuit priest… how can I understand that [the Holocaust]. [The priest responded]… as a Catholic…all I could do was make amends to those who are harmed,” Wollschlaeger said. There was a progressive Catholic church near Wollschlaeger’s hometown that invited both Jewish and Arab Israelis to Germany every year to meet with Germans. This program was meant to build peaceful and personal relationships. Wollschlaeger participated and, through this program, became infatuated with an Israeli girl he met.

In order to see her again, Wollschlaeger journeyed to Israel and was hosted by her family. At first he was tentative, worried that he would be recognized by one of his father’s victims. However, through the father of the girl who learned German after being in a displaced persons camp following the war and his imprisonment in concentration camps, Wollschlaeger began to learn about the Holocaust.

“I gained access to this horrific, unbelievable manslaughter committed by Germans, my people, my responsibility and I emotionally broke down. And I asked myself, how could those people rebuild their personal lives, their professional lives, rebuild their old country anew? How can that be? Where do they get the strength from? Who are those Jews? I want to find out about what they are about,” Wollschlaeger said.

Wollschlaeger returned to Germany in the late 1970’s and found a small community of Holocaust survivors who kept a synagogue in his hometown. He told his story and told the rabbi he wanted to help. In exchange for instruction on the Jewish faith, he became a Shabbos Goy, or a non-Jew who performs work for OrthodoxJews on the Sabbath. This was the beginning of the process of joining the Jewish community.

Over the next few years,while in medical school, he would be disowned by his parents for missing Christmas in favor of keeping Sabbath. The Jewish community gave him financial support and welcomed him to participate in the burial practice of their rabbi. After this, he expressed a desire to convert and had to deal with strong skepticism from the community. Through all this, he eventually passed a grueling, hours-long interview and joined the Jewish Orthodox community in 1986.

At the age of 29 years old, he moved to Israel, renounced his German citizenship and was promptly drafted by the IDF. He served as an army medic for several years and suppressed his story, not wanting his past to get between him and his company in the middle of battle. He did not talk about his life or his family history until his son asked him about his grandparents. This was the beginning of him traveling the world and telling his story. He traveled back to Germany

and visited his parents’ graves, which were in the shadow of a wall separating the Christian and Jewish parts of the cemetery.

“My parents never stepped out of the shadow and, even in death, they rest in the shadow. And I had to step out of the shadow, look back, learn the lessons. You cannot change the past. Move forward so that it can never happen again.And that’s what I did,”Wollschlaeger said.

He concluded the discussion with a denunciation of hatred in any form, citing several stories of hatred encountered at his private practice and modern-day anti-Semitism. In response to a question about Jewish life in modern day Germany, he stated in no uncertain terms that America, not Germany, was the source of the majority of anti-Semitism in the Western world and that the media and Internet “lowered the threshold” of anti-Semitism and hatred.