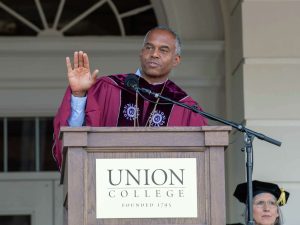

Police Chief Eric Clifford ’94 talks about policing culture in Schenectady

Schenectady Police Chief Eric Clifford’94

June 12, 2020

With widespread protests across the United States against the murder of George Floyd by an officer from the Minneapolis police department, the power held by the police and systemic racism in the U.S. has been brought into question. Concordiensis reached out to Schenectady Police Chief Eric Clifford ’94 about policing in Schenectady. Recently, Clifford was a panelist at the discussion about “Racial Injustices” that was organized by Union College on June 4.

In the panel discussion, Chief Clifford talked about how he is taking steps to improve the relationship between the police department and the Schenectady community. These include a more rigorous routine of filling out the use of force forms which are used to record any physical engagement of officers while on duty. “Use of force forms are a requirement of the Schenectady Police Department in order to comply with our Use of Force policy,” Clifford told Concordiensis. As of May 31, 127 use of force reports were completed, according to Clifford. In 2019, there were 267 use of force incidents as compared to 2016 when the number of such cases was 420. “This is representative of the efforts we have made since I became Chief of Police on September 13, 2016,” Clifford said.

Previously, he had acknowledged that there have been incidents of police brutality in Schenectady. The most famous one being a case of excessive force filed by Nicola Cottone against police officer Mark McCracken and the city in 2016 which resulted in a $336,000 settlement in 2018, according to Daily Gazette. A report dated September 30, 2016 states that McCracken used excessive force against Cottone while she was handcuffed resulting in a significant wound to her head, the Gazette reported. The report, which was included in a filing in March, did not detail what, if any, punishment was issued to McCracken who was even a finalist to become chief, before Clifford was selected for that post according to the Gazette. In April 2019, McCracken retired from the force, the Gazette reported.

When asked about the outcomes of the cases of police brutalities in Schenectady, Clifford told the Concordiensis via email that “all [cases] resulted in the officers resigning or being fired.” “They also resulted in organizational changes- policy, procedure and equipment related. There has also been training completed after various cases- de-escalation training, verbal communication skills training, implicit bias and procedural justice training to name a few,” he said. Recently, the legal doctrine of “qualified immunity” has also come under scrutiny over concerns that it makes it harder for officers to be sued in cases of excessive use of force. Under federal law, it shields government officials from being held personally liable for actions performed within their official capacity, unless their actions violate “clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known,” according to the Washington Post. When asked about his opinion on qualified immunity, Chief Clifford said that he supports the doctrine since it is “a necessary legal protection for police officers”. “The legal doctrine does not protect officers who break the law or violate a person’s civil rights. Without this protection, police officers open themselves personally to lawsuits that may be frivolous and/or cases where good faith judgment was used and was incorrect,” he said.

In the panel discussion, Clifford had also talked about the “field interviews” that are conducted with Schenectady residents. He said that they are conducted to record essential documentation about contact with the members of the community. “We also want that documentation to be valuable to us if needed for criminal investigations. Persons interviewed typically exhibit some suspicion, but don’t necessarily have to be in [the midst of] the act of committing a crime,” Chief Clifford said. Prior to his appointment as Chief of Police, there was a strong push by administration to produce field interview numbers, according to Clifford. However he began “focusing more on quality than quantity,” in an effort to make members of the community feel more comfortable in “walking and interacting without the fear that the police will stop them and ask where they are going,” according to him. “In 2015, we had 2,356 field interview stops. In 2018 that number was 1,344, and in 2019 1,107. In 2020 [as of June 9] that number is 289. This number is low due to COVID-19,” he said.

Moreover, Clifford had mentioned that amongst those stopped most often by the Schenectady Police, most had been suffering from some form of mental illness. In a bid to improve the situation, the police department has yearly training on how to handle crisis situations with people who may be suffering from mental illness. “We have also been trained on how to deal with non-verbal members of our community (autistic),” he said.

Chief Clifford also shared details of the recruitment procedure for the department. To become a police officer one has to achieve 30 credit hours of college from an accredited school, then sign up with civil service for the exam which is “typically given every two years and once scored,” according to Clifford. “The process includes a written application, formal interview and psychological examination, polygraph examination, and thorough background and character investigation. The successful candidates are vetted by myself, the commissioner and mayor before being hired,” Clifford said. The Zone 5 Regional Law Enforcement Academy runs two times a year and provides basic law enforcement training overseen by the NYS Bureau of Municipal Police (BMP), according to Clifford.

Recently, Chief Clifford made the headline in the Daily Gazette for taking a knee with the protestors in Schenectady on May 31. He shared that this was when protestors came to the police department and asked that he come out and speak to them. He was subsequently asked to take the knee. “I agreed to take a knee with them to show that I cared, that I recognize the pain and emotions that they were going through and to continue to build trust with the community that I serve,” Chief Clifford said.When asked about the impact of moments like these he said, “I would like to think that they have an impact- whether small or large. I also recognize that the simple act of taking a knee is not enough. Dialogue, communication, and change needs to occur. “