Interview: co-creator of Wikoff exhibit on methods & morals

September 19, 2019

Q: So, tell me about The Weight of This.

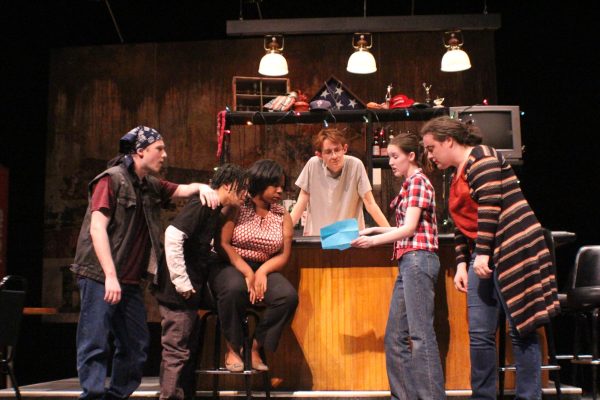

A: The Weight of This is the student exhibition on the third floor of the Nott that holds my work, and the work of Tina Tully. My work in the exhibition deals with topics of sexual assault on campus through an empathetic lens. I’ve utilized graphic imagery and short prose length in order to emphasize certain details of the work. The project was about giving a voice to those who are often voiceless. I also hoped that the project would be reflective of the experience of my peers, thus bringing traumas that are often only spoken about in the dark into the spotlight.

Q: What were some of the processes involved?

A: The book of prints originated as the focus of my Scholars Project. For that I wanted to work in the mokuhanga format, which is a form of ancient Japanese printmaking that utilizes haiku with imagery .

For the book I sent out an anonymous survey link on my social media pages asking young women and men from my campus to anonymously share their stories with me and to also share quotes that their attacker had said before, during, or after the incident had occurred. I then turned them into haikus. I tried to keep the original wording as much as possible. Then I formulated the images from the poems, turned those into prints, and tried to weave the stories into a timeline.

It was really important for me for the process to be as natural as possible, that’s why I preferred to do the form of Japanese woodblock printing as a form that differs from Western styles of printing that tend to use more chemicals. The only difference is that the woodblocks traditionally are hand-carved but I laser-cut the wood blocks, instituting newer technologies into a traditionally natural process. I then hand-carved each of the texts, hand-bound all of the books, and hand-printed everything.

Then I took all of my additional prints and I used those for the murals, and than in the mural, I wanted the mural to compare and contrast how women are portrayed in popular media and the psychological effect that this has on women, and juxtaposing that with the prints. I also wanted to create something interactive for the audience to try to make it as personal of an experience as possible.

Q: You said that a natural process was important to you. Can you elaborate?

A: Generally, I prefer working with natural materials. I do prefer water based material. Water is something that is part of all of our lives, and a water-based process is very personal, it’s very quick, and it requires a lot of focus and attention to detail.

Q: How long did the project take you?

A: I started it September 2018. I began collecting the poetry and binding the books at the end of winter term 2019. It took about six or seven months for the books. I started the mural in June of 2019, and then I installed it on the spot.

[Co-creator Tina Tully’s work] deals more so with body image, it being the fiftieth year of women at Union, we wanted to focus on issues that women deal with on this campus, and body image and sexual assault are two issues that tend to go hand in hand. One can feed the other, especially on a college campus.

Q: In the mural, what media did you draw from?

A: I sourced most of the base imagery from magazine advertisements from the fifties and sixties, because I noticed a lot of those magazines portrayed women as being housekeepers, a lot of literal imagery of women serving and bending over to men, and being commodified and objectified. I also took from modern magazines to show how the objectifying still happens. Even though we tend to see an empowered sense in which we see a woman on the cover of Sports Illustrated, you say, oh, she’s empowered, she’s reclaiming her sexuality, but in the eyes of somebody who does not have that sense of empathy, she is still an object, a commodity, and in some sense has a dollar sign on her, essentially.

Q: How did you go about the process of creating a visual aspect for each haiku?

A: I’m really inspired by Perenial’s idea of the collective unconscious, how there are collective symbols that all of us recognize regardless of what language you speak or where you’re from we all tend to recognize similar symbols and similar shapes and structures tend to evoke very raw emotions out of people. When I was creating the images, I would create a haiku, and then due to the graphic nature of the poem it would create raw primal imagery. I wanted to make an image that is primal and raw to reflect on a primal action, to capture that immediate intensity, and that spur of the moment.

Q: How do you think people will react to your work?

A: I wanted the images to exist in a space between abstract and directly representative of the specific assault, so that there was room left for interpretation for each individual viewer. So, reactions will probably be on a person-by-person basis, but my hope is that the exhibit will at the very least create a sense of empathy in those who can not put themselves in the shoes of young women, particularly those on this campus, and I feel that our project altogether facilitates that empathy.

“The Weight of This” will be on view through February of next year.

Wayne Mcpartland • Sep 27, 2019 at 7:58 am

An extremely important subject and to be reflected in art is a creative way to emphasize what abuse really is. Lily, great job.