Tickled Pink: Twenty years of “But I’m a Cheerleader”

April 28, 2019

In 1999, five years into the U.S. military’s Don’t Ask Don’t Tell policy and 16 out from legal gay marriage, the satirical independent film “But I’m a Cheerleader” premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and was subsequently barraged with negative criticism. The film establishment deemed it too garish and too gay to appeal to mainstream audiences, so it was naturally snatched up by fans of independent and LGBT films, who elevated it to cult classic status.

“But I’m a Cheerleader” stars Natasha Lyonne (“Orange is the New Black”) as a straight-edge high school cheerleader whose parents send her to a conversion camp for LGBT teenagers.

What makes it special is that it’s executed less like A24’s 2018 drama “Boy Erased” and more like if Tim Burton had directed “Pretty in Pink.” It’s an indictment of institutionalized homophobia using candy colors and outrageous caricatures, which come together to showcase the absurdity in trying to change nature. Jamie Babbit in her directorial debut (of full-length films) does not leave any element un-satirized save for the teenage “campers,” a bold statement that solidified “Cheerleader”’s place in the independent film canon for 20 years.

Though LGBT cinema and lesbian representation in particular has transformed drastically in the past two decades, the film community would do well to recall this film’s playful radicalism and the space it created for gay kids to be sarcastic, soft and strange all at the same time.

The actual premise is a dark one. The film’s fictional conversion camp is based on the real-life Exodus International camp, which operated until 2013. A “New York Times” report on the recent history of conversion therapy defines it as “discredited psychotherapy methods that aim to change a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity,” referencing the fact that prominent medical associations have taken a stance against the phenomenon’s effectiveness and ethical ramifications.

The report also calls attention to the website for Vice President Mike Pence’s 2000 congressional election campaign, on which he suggests his support for conversion therapy. Given that he has not explicitly conveyed otherwise, we can assume he still holds this opinion. That alone should be enough to stress the importance of this film as a tool against reigning attitudes toward LGBT youth.

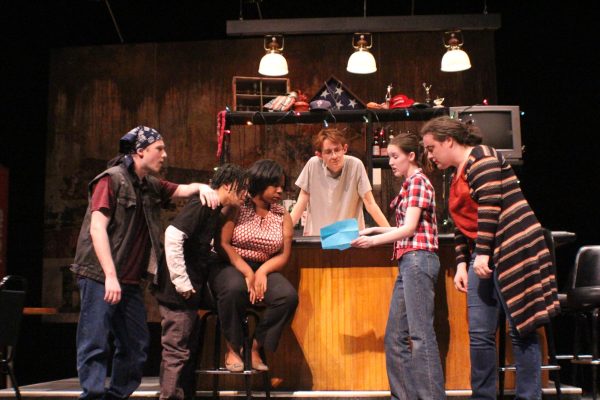

“I myself was once a gay. Now I’m an ex-gay, Megan. I work for a place called True Directions who help people, like yourself, to learn to understand the reasons behind homosexual tendencies and how to heal them,” says a camp counselor played by RuPaul, young and out of drag, to the protagonist. He has a clipboard, a blue shirt and tiny blue shorts, and stands in contrast to the camp’s head honcho Mary Brown, a Cruella de Vil-esque figure who dons a bright pink suit and toes the line between well-meaning pedantry and pure viciousness.

The rest of the camp is similarly outfitted: pink and blue group therapy sessions that feature everything from pinpointing the “root” of one’s homosexuality to learning to occupy traditional gender roles, which means chopping wood for the boys and cleaning a kitchen for the girls. The “campers” bond through this shared cruel and unusual punishment — the more they have to work together in ridiculous situations, the stronger they grow as friends, or more.

The teenagers in the film are the only element to escape the lurid aesthetic choices that exaggerate the unnatural environment. Once the oddballs themselves, LGBT teenagers are now the new normal, as they become the characters with whom we identify and through whose eyes we see the preposterous features of the film’s setting.

Whether this was intended as a conscious reversal of the norm or a way to fashion the audience into outsiders themselves is unknown, but regardless, it produces the desired effect: Babbit, who identifies as lesbian, stated that the film was intended for a lesbian teen audience, a rarity among LGBT films, which are often marketed to twenty-somethings with a penchant for storylines and production outside the mainstream. “Cheerleader” is different; the specific production choices ensure the subjects’ real-world counterparts are included in the fold.

Since “Cheerleader,” “lesbian cinema” has gone through many iterations and not all of them good. “The L Word” (2004-2009) attempted to pay tribute to lesbians living fulfilled lives, but it drew criticism for the lack of diversity in the cast and in its portrayal of lesbian characters (all but one were conventionally and even hyper-feminine). It has also been accused of catering too heavily to the male gaze in a manner similar to that of 2013’s “Blue is the Warmest Color,” which had a majority-male production team.

Nonetheless, the consensus is that LGBT representation, especially for lesbians, has improved considerably since Lyonne and Clea DuVall brushed hands while washing dishes at True Directions. In 2018 alone, four films received critical acclaim for their representation and cinematic excellence: “The Favourite,” “Disobedience,” “The Miseducation of Cameron Post” and “Rafiki,” though there were arguably many others. Cheerleader had an NC-17 rating despite having no nudity or explicit references to NC-17 activities and a few scenes had to be cut at the direction of the Motion Picture Association of America. Today, the restrictions are much looser.

The films mentioned above have enjoyed considerable creative liberty in telling their stories and some have even drawn from the lesbian film canon to obtain the desired effects. “Rafiki” conveyed romance with a pastel pink tinge and “The Favourite” did not shy away from caustic dialogue that matched the unapologetic nature of the genre.

Maybe you won’t watch the movie. But if you like cultural touchstones, or you’re just looking to poke fun at someone who deserves it, this film begs a viewing. Nothing communicates the film’s joyfully arresting quality like Lyonne’s recollection of its first days on the scene: “I remember Clea [DuVall] and I went to Sundance together and a lot of the Mormon girls were coming up to us. Clea and I would be crying because it was so moving that they had come out because of that movie. They had never seen anything like it.”

Trust them — you have never seen anything like it. Go on, dive in.